Why would we need another style of Bible study? Let me tell you why, in this introduction to my new concept of “Creative Margins,” an imaginative and playful way to engage with scripture, drawing on the practices of medieval Christians.

Creative Margins Bible Study: Colossians Workbook: Introduction

Bible study calls on so many different mental processes! We observe, we analyze, we research meaning and context and interpretations. We tap into our emotions and our lived experience as we apply scripture to life.

But how often do we listen to the scripture with our imagination? We need to engage scripture with that playful and childlike part of our selves that loves fiction and pictures and music and jokes and crossword puzzles. If we want to desire God with all our hearts, we must use all our hearts in scripture study: not just our intellect or moral reasoning, but the playful side of our hearts. We must use our imagination.

Do we really need another style of Bible Study?

When I was in college, I was introduced to an inductive method of Bible study called “manuscript study,” and it changed my life. It took the same intellectual tools I loved to apply to literature–looking for patterns, asking questions–and applied them to the Bible in a structured and visual way. It cleared the way for us to read the Bible slowly and engage some of our natural intellectual curiosity and creativity. One of the rules I was taught for this kind of study was that there should be no reference to other texts, just a commitment to look at what was in the passage before us. This not only leveled the playing field in groups, but also encouraged laying aside assumptions and engaging deeply. And while I have heard many people struggle against this rule over the years, I still believe it is a necessary step as we first seek to understand a passage of scripture.

But of course, our first effort to understand a passage will not be our only encounter with it.

When I was a graduate student, learning about medieval Irish literature, I was surprised to find that some of my favorite poems–which I first encountered in edited anthologies–were actually written in the margins of other documents. A tender, personal song to the baby Jesus, for instance, is found in tiny handwriting on the edge of a page about the calendar of the church year*. Many of the phrases and sayings we used to study the vernacular language were drawn from “glosses” or notes on pages of scripture texts or commentaries. Others before me had loved writing in the margins of their pages! But their comments were not so tightly focused as mine. Even when they were introducing and commenting on the main text, they often seemed tangential. Indeed, scholars of the 19th and 20th centuries sometimes mocked those “scribes,” whose additions seemed to always “miss the point” or be “errors,” despite the fact that they were using precious materials and years of training. And then I read an article** that suggested that these much-maligned scribes were scholars with a different kind of approach: one open to many overlapping parallels and in fact a whole web of connections and meanings. I began to wonder what it would have been like to be a scholar in those days, and whether I could ever “study” in such a discursive, imaginative way.

This year I have been reading Mary Carruther’s book on medieval Christian meditation and composition, The Craft of Thought: Meditation, Rhetoric, and the Making of Images, 400-1200 (1998). Carruthers argues that medievals saw thinking about scripture as an act of invention. They used the “inventory” of texts, ideas, and images carefully stored up in their memories, and made creative connections. Allegory and metaphor are constant in their teaching. So are what we might call “puns”–connections made just on the basis of sound, which (as many preachers know) are easy to remember.

What if we let ourselves make connections to other texts we know? To other Scripture passages, and also to novels and movies and artworks? What if we took time to explore the “random” connections formed by the sounds of the English translation, or the events of our own day? This might break us free of the need to control the experience, to find something “useful” in the passage, to “make meaning” in the humanistic sense, which can be a great (unconscious) burden.

But should we “play” with Scripture? Wouldn’t that be childish or disrespectful? It certainly would, if we were simply using the scripture for our own ends. I am using the language of play, however, not to indicate an absence of thought or a self-centered domination, but rather a loving receptiveness. There are modes of learning that our post-Enlightenment culture cuts off and scorns. It may be that the last time you “knew” something through a focused and effortless association and recombination was as a child at play, but that is in fact a good and time-honored way to “know.”

There are many good ways to study scripture. I don’t believe that this method I’m experimenting with is “the right way.” As Colossians 2 tells us, “holding fast” to Jesus is what matters, and not the methods or rituals. I have benefited greatly from inductive study, commentaries, sermons, memorization, journaling, discussions, and lectio divina. If we are to meditate on scripture “day and night” we have time for many methods! But if we are to come to love Scripture more and more, we will need to spend time with it–relaxed and happy time with room for the Holy Spirit to move. Carl Jung once wrote, “The creative mind plays with what it loves.” Does your current play reflect a love of the Bible? James K. A. Smith writes, “discipleship, we might say, is a way to curate your heart, to be attentive to and intentional about what you love.”

How this book is set up

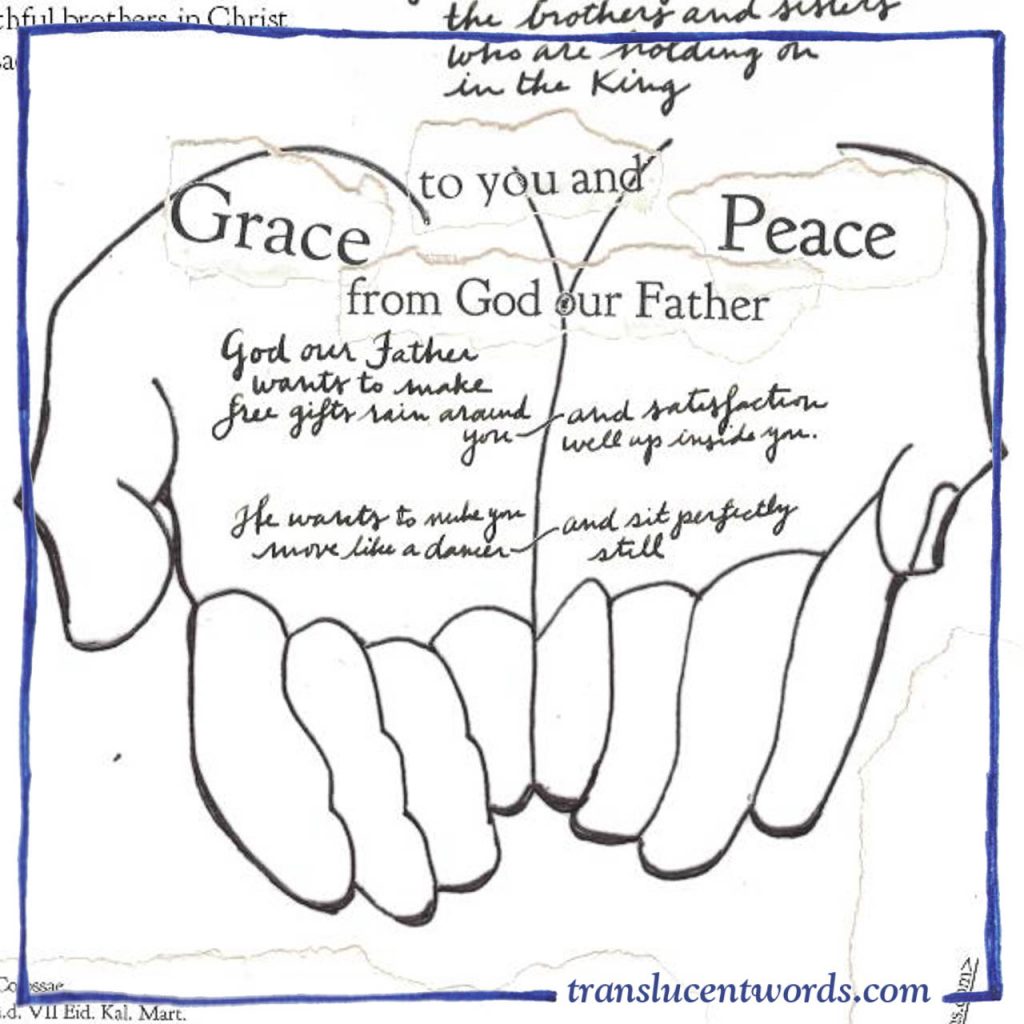

The most important part of this book are the pages at the end, with a few verses each in large print and huge margins for you to “play” in. Creative play cannot happen in a vacuum, though–boundaries and guidelines and models are crucial to being able to start. Games have rules, no matter how arbitrary. Artists respond to conventions and role-models, even when they react against them in a new direction. The first half of the book is here to give you guidelines and examples as you get started. For each short section of Colossians, I have described how your process might flow–starting with questions and close observation, and then moving on into the realm of imagination. Then I provide some “warm up” questions, for you to practice the skills of this kind of textual play. And finally I will give my own glosses on the same text–cleaned up and hopefully legible!

Notice that I suggest starting any “Creative Margins” time with close observation of the text as it stands. It can be easy to fall into the trap of ignoring the scripture itself, and simply exploring your own thoughts and feelings–many good Bible studies have been derailed by flights of “imagination” that did not involve listening to the text. It is better to “feed” your imagination first, with deep and careful reading, questioning, and understanding. When you know the text, like you know a person, you can engage in an enjoyable conversation–even a teasing, or silly, or challenging conversation–and still show the respect you would for a person. We must resist the temptation to manipulate, control, or force our own vision. If the Bible is truly an authority in your life, it needs to be treated like a respected mentor–but the kind of mentor you can laugh with and be comfortable with for hours on end.

I hope that you and I both will spend many happy hours in the presence of our Lord.

*”Ísucán” found on January 15 of the Félire Óengusso (“Martyrology of Óengus”)

**Morgan Thomas Davies, “Protocols of Reading in Early Irish Literature: Notes on Some Notes to Orgain Denna Ri/g and Amra Colum Cille,” Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies 32 (Winter 1996).

Creative Margins: Hello From Paul (Colossians 1:1-2) - Translucent Words

[…] Here is the first study on Colossians, using my Creative Margins method. […]