This week I decided to read John Milton’s poem “Lycidas,” which I saw praised as the greatest elegy in English. But as I stepped into the poem, I felt disoriented–I felt, I imagine, as Milton might if he stepped into Disneyland. I could enjoy the beat, I could get a sense of what was going on, but all around me were a hundred stories I didn’t know and couldn’t respond to. In the seventeenth century, a poet could write a “pastoral elegy,” and know that the literati reading had read hundreds of similar poems. They not only knew the format and conventions (as we do for contemporary movie forms), they had read or even memorized thousands of years’ worth of this kind of poem in Greek, in Latin, in the vernaculars of the Renaissance.

In that kind of tradition, I imagine, every line is full of jangling bells and humming echoes of other lines, other moments of emotion in the reader’s life. The whirlwind of characters from mythology and literature can flash through the poem bringing the scent of many stories. Just imagine the power of writing into a tradition like that, where the form must be tightly controlled and traditional because everything means so much: like a firefighter’s precise motions with a power hose, or a singer in a stone chapel with echoes bouncing off the wall. And the poet tries to control all that storm of tradition, and meanwhile speak a truth beautifully.

But I’m wondering now–with the perspective shift that comes from examining something foreign–do I write within a dense tradition myself? I need to consider the weight of the formulas that shape Internet writing (or parenting, or small talk) in our culture. Can I ride that storm of tradition better, and speak one truth at a time with grace?

Because “Lycidas” has left me in no doubt that the beauty of words matters. Milton’s indictment of clergy who are in it for themselves and feeding on their flocks jumps right to their words, their “songs:”

…their lean and flashy songsGrate on their scrannel pipes of wretched straw,The hungry sheep look up, and are not fed,But swollen with wind, and the rank mist they draw,Rot inwardly, and foul contagion spread…

Lean and flashy songs don’t feed those who listen–worse than that, they cause spiritual rot. In contrast, the inhabitants of heaven who greet Lycidas as the poem ends seem to move together in a kind of singing dance:

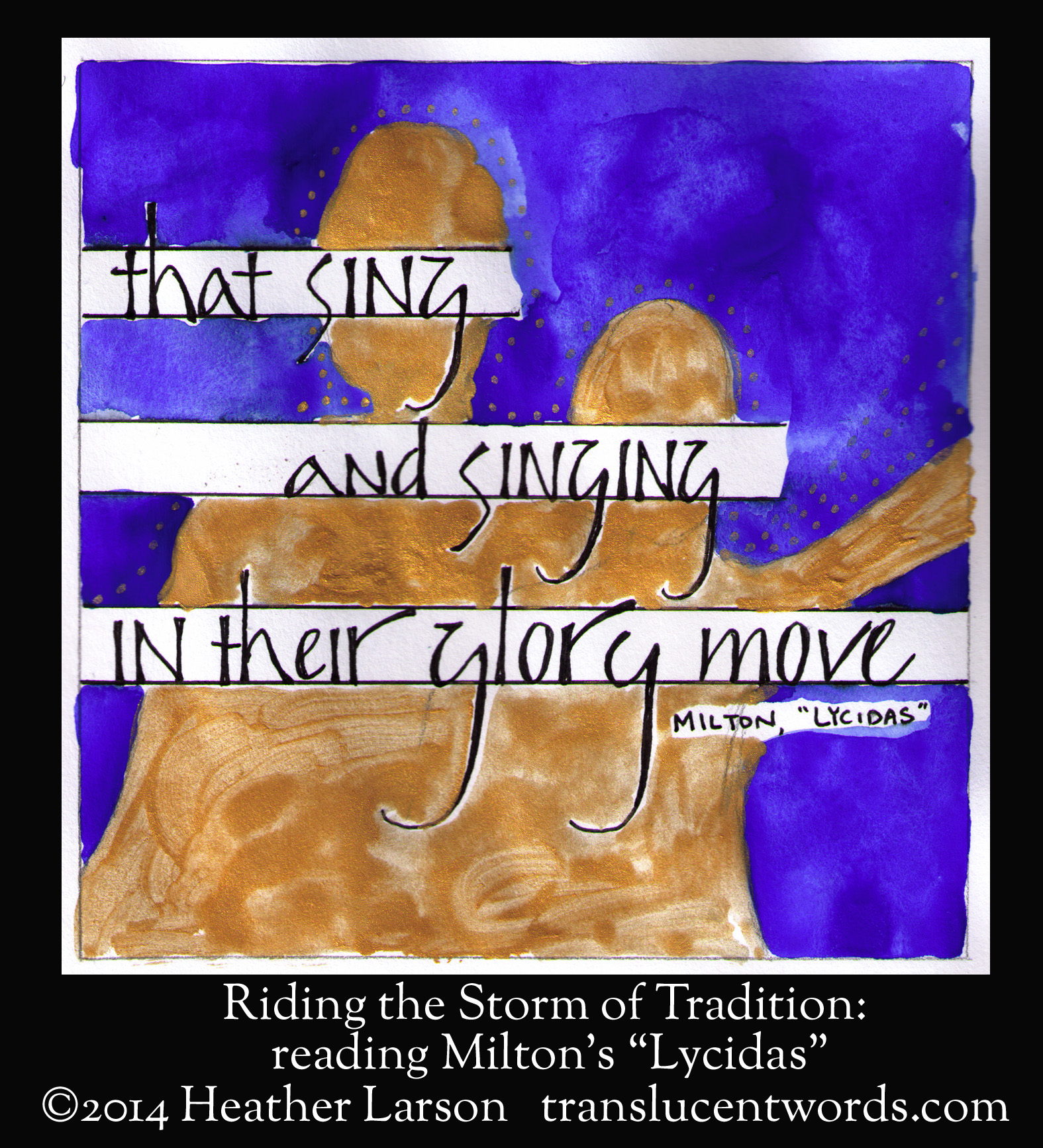

There entertain him all the saints above,In solemn troops, and sweet societiesThat sing, and singing in their glory move…

May we all sing well, as we dance the steps of our moment and our culture.

Leave a Reply