How do you get started, reading old books? It might not be as easy as it sounds, even for those who believe in its importance… Here are some ideas and tips for Charlotte Mason homeschoolers who are practicing “mother culture”—the deliberate effort of the teacher to grow in learning and wisdom for herself.

Old Books & Mother Culture

“It is a good rule,” wrote C. S. Lewis, “after reading a new book, never to allow yourself another new one till you have read an old one in between.” We mothers who are trying to implement a Charlotte Mason education are no strangers to the benefits–and pleasures–of old books! I would be preaching to the choir if I wrote now about why we should read books written before, say, 1900. And we in Sursum Corda have many resources about how to do it with our children–including the rich resource of each other. But I am wondering about those little moments of mother-culture reading time we carve out for ourselves. Has anyone else found that it takes some effort to maintain a good ratio of old to new books in your personal mother-culture reading? We are flooded with articles and new books that sound fabulous, directed straight to the perceived needs of people like us. We are intimidated by the weight of years that hangs on Homer, by the unfamiliar world-view of Milton, by the archaic language of Spenser. We are unsure which authors to read, or which translations. If you, too, have found that finding old books for mother culture takes some effort, I’d like to offer some strategies that have worked for me.

Find a “friend” to introduce you

I am going to go way out on a limb here and dare to contradict C. S. Lewis! In the same beautiful introductory essay that I already quoted, Lewis argues that the old classics are actually more approachable than the modern books written about them. I thoroughly agree that we must avoid “some dreary modern book ten times as long, all about ‘isms’ and influences and only once in twelve pages telling him what Plato actually said.” But in honesty I must tell you that finding the right modern books has made all the difference for me. Which are the right modern books? Those written by someone I can connect to, who happens to deeply love the old book in question. This is not a matter of comprehension–of my having enough background to read the old book–it is a matter of affection. As a parallel, I think of my reaction to cricket scenes in P.G. Wodehouse. I know almost nothing about the sport of cricket. I have tremendous trouble keeping my eyes focused on a game in any sport, even when my own child is playing and I’m trying very hard. But I have found myself actually getting excited about a minutely described cricket game in a Wodehouse novel, because I am seeing it through the eyes of an author who loves it. We read with our hearts, and not just our brains.

How does this play out in my reading of old books? Let me give two recent examples.

Last year, as I prepared to read the Odyssey for our homeschool, I found the book Homeric Moments: Clues to Delight in Reading the Odyssey and the Iliad, by Eva Brann (2002). I started in the summer as I prepared, ran out of time, and ended up reading it in twenty-minute snips all year long, as part of my mother culture time. Brann is immensely knowledgeable about Homer, but more importantly to me, she really does take “delight” in this reading. Her fond reflections on Odysseus made him someone I wanted to meet. Her theories about the structure of time, her excited musings about the effect of the long similes or the description of the decoration on a shield…made me feel excited when I came to those passages. When I learned to drive a car, the hardest part for me was learning where to put my eyes when–of all the data coming at me, what was significant. Brann taught me where to put my eyes when I read Homer. I had read the Odyssey four years before, with my older daughter, but now my reading was completely revolutionized.

This year, teaching Renaissance history for Sursum Corda, I picked up a book called The Elizabethan World Picture, by E.M.W. Tillyard (1959). It was short, and well-written, and I thoroughly enjoyed grappling with the aspects of world-view he brought out; I hope that it influenced the quality of my teaching! But it also had this interesting side-effect: it made me want to read some of the plays and poems he quoted. I found myself unexpectedly immersed for a couple of days in Milton’s Comus, a short play I had never heard of. I found a copy of Spenser’s “A Hymne of Heavenly Love,” and a certain poem of Alexander Pope, whom I had never really read. I met these works through quotes, pulled out and displayed by someone to whom they were old friends. And so I walked into them already knowing that I would like them. In a sense, I was like the lady of virtue in Comus, walking into a sinister wood with confidence; the evil being watching her remarks in wonder, “Such sober certainty of waking bliss / I never heard till now.”

“Read upstream”

Milton, and Spenser, and Pope, in that example, were just passing fancies, read as rabbit trails and thoroughly enjoyed. But a related strategy which works for finding whole new authors to read in depth is to “read upstream.” I can no longer remember where I first heard of this strategy, but I can tell you that it has brought me great pleasure! The idea is to find an author you love to read already, and to deliberately figure out who that author loved to read. And once you fall in love with one of his favorites, ask the same question of your new favorite. So, who did C. S. Lewis love to read? Vergil, Boethius, Spenser, Milton…the list would be long, but those are some of the authors I have read because Lewis loved them. Who did Milton read? Vergil, Spenser, Shakespeare, Calvin… Reading upstream is a delightful way to get wet, without feeling that you need to see the whole river first.

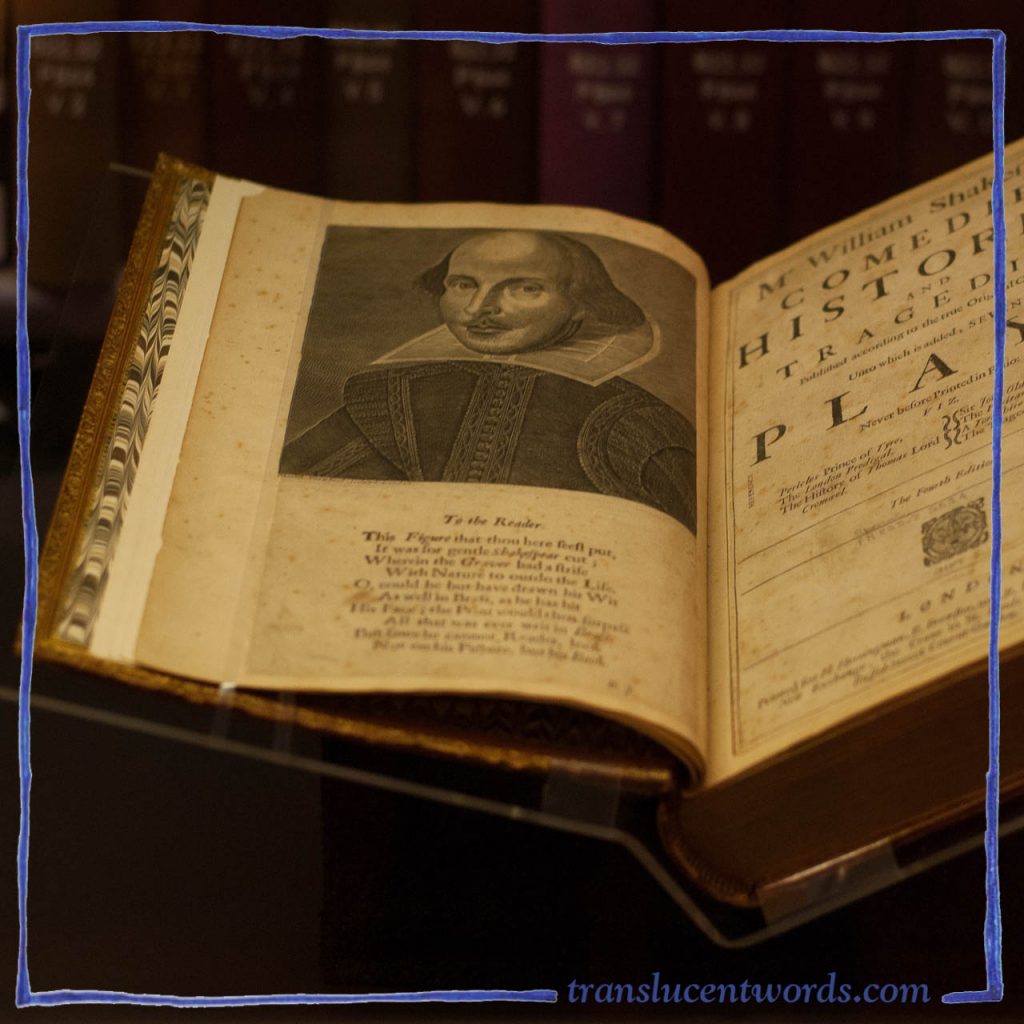

Read with your ears

We all know that a read-aloud can be enjoyed by a child who could not possibly read the same book independently. The phrasing, the emotion, the reactions that the reader injects in the process of reading aloud clear away obstacles to understanding. How can we use this effect for ourselves, in our mother culture? For me the clearest example of this is Shakespeare. I worked my way through some Shakespeare plays in high school, as many of us did, and enjoyed them moderately, with effort. But in 1993 I walked out of a theater in love–with the Kenneth Branagh version of Much Ado About Nothing (and my soon-to-be husband, but that’s another story!). Over the years I wore out at least one recording of that movie. Then we moved to a town with live Shakespeare every week in the summer, and began to go to both plays each year. By the time my girls became teens, the family went to each production multiple times each year…and the girls were in productions of their own. The whole thing just mushroomed, for us. But what I can tell you, looking back from here, is that it is incredibly helpful to watch the play (or at least to have watched many other similar plays) before you read it. Having understood the words with the aid of all the phrasing and drama that the actors contribute, you will understand them far better in print. I have not explored audiobooks very thoroughly, myself, but I think an audiobook by an author who understands and loves the text would be a similar incredible entrance into an old book with difficult language.

Re-read

In language pedagogy, it is now accepted that fluency develops from hearing or reading a word or phrase many, many times. Reading that uses the same words you have already encountered is incredibly valuable for developing skill in language use. And there is nothing that can give that effect as well as a book you have already read! So if the book you love most from the 19th century is Pride and Prejudice…read it again! Read the books you love on a regular schedule, and you not only enjoy yourself and find whole new insights, you also expand your capacity for the language of that time period more than you can imagine.

We have access, today, to as many grand old books as there are stars in the sky. I have a library on the cell phone in my pocket that would make a Renaissance gentleman swoon. And we need those old books; we know we do. Old books feed us just as deeply as they do our children. What we do not have is homeschool mothers of our own, to find the perfect books for us, introduce us to them, and (to be honest) require us to keep reading when they are not easy. As I look back over all these strategies that have worked for me, it seems that they all involve finding a mentor to act as that “mother.” Whether it is a modern book that I connect to, a favorite author whose taste I can follow, an actor whose voice will make a way for me, or even the familiarity of a book I already know, I can find a “mother” somewhere in the riches of our “culture.”

Works Cited

- C. S. Lewis, Introduction to Athanasius’ ‘On the Incarnation’ available on the Internet (just the introduction) or on Amazon

- Eva Brann, Homeric Moments: Clues to Delight in Reading the Odyssey and the Iliad (2002) — on Amazon

- E.M.W. Tillyard, The Elizabethan World Picture (1959) — on Amazon

Leave a Reply