This article about the “wonder” in learning Latin first appeared on the website of the Sursum Corda homeschool community.

What do you think of, when you hear the word “grammar”?

As a child, I picked up the attitude from adults that grammar was dry and boring and hard–a set of facts to be memorized so as to be “correct.” Some adults thought it was useful, others thought it wasn’t, but they all seemed to agree that it was dry and difficult.

As an adult, wading into the world of homeschooling, I read about the “grammar stage” of childhood, when students should stuff themselves full of facts, before they were old enough to think deeply about them. Classical Education has matured, and so have I. Instead of a time to stuff, the grammar stage can be seen as a time to observe closely with curiosity, and absorb whole ideas before analyzing them. And while it is crucial to early childhood education, we now see it as the first step in any real learning, the driving motivation behind any interpretation or application. Every day now, I try to ground myself in this kind of “grammar”–what James Taylor calls “poetic knowledge”1–and it is full of wonder.

But how does that connect to the literal meaning of grammar? Where is the wonder in tenses and persons, and agreement of adjectives?

Grammar in this original sense is the careful observation of words. Words in themselves are amazing, when you stop to think about them–how much meaning we can convey in only a sound or two! As Sami pointed out in the Mother’s Course, Charlotte Mason wrote that a child “knows, as we have forgotten, that the epithet ‘mere’ is the very last to apply to words.”2

Imagine for a moment that you are on a nature walk with a child, counting petals and touching leaves to feel the furry texture. You come to a patch of Latin words. “Look, Mama, there are so many of these words that end in ‘-ibus.’ What a funny sound!” After you honk “-ibus” at each other a few times, the two of you figure out that all those words are translated “to the –s” in English. “But wait, Mama, that one over there means ‘to the boys,’ and it doesn’t end in ‘-ibus.’ Why?” Now, if your Latin skills are similar to my nature skills, you know the answer to this: “That’s a great question! Let’s go home and look it up.” (If you don’t know where to look it up, text me. I’ll text you back with a nature question the next week!) It turns out that with grammar, as with everything else, wonder is born from close and loving attention.

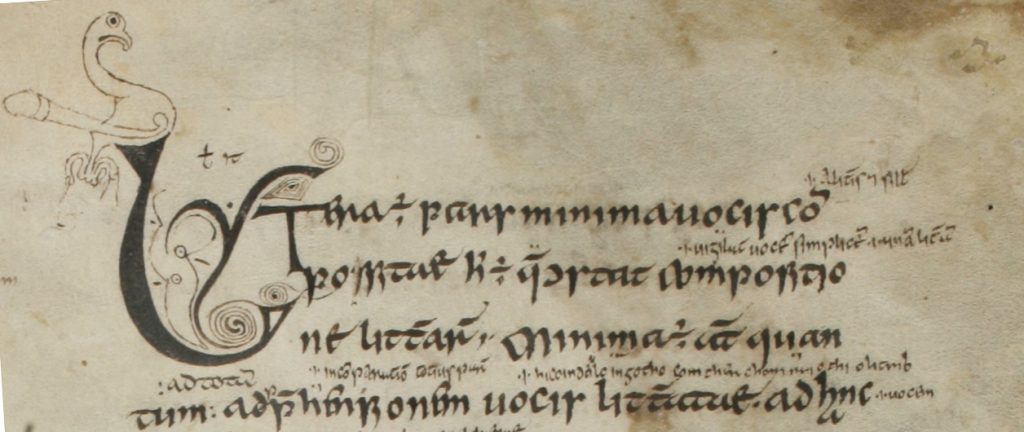

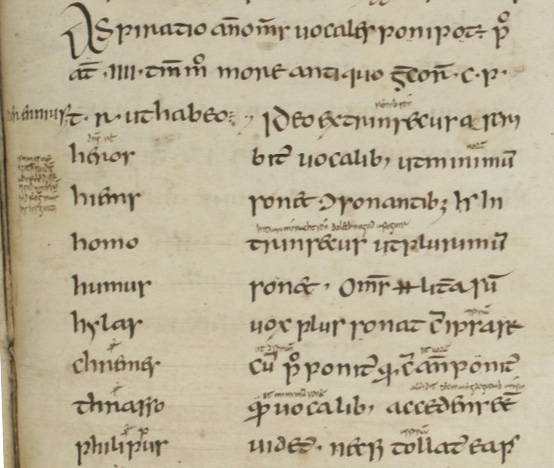

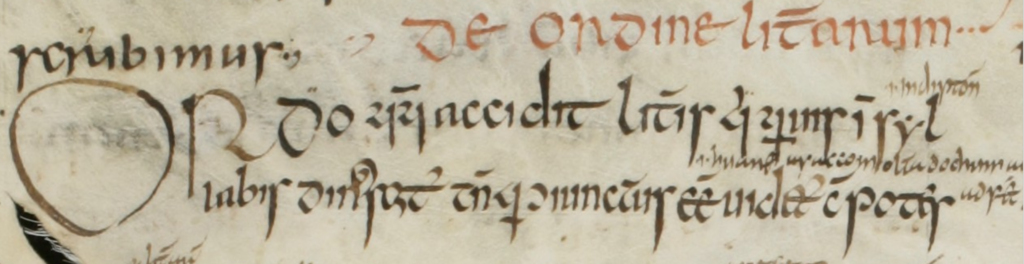

But is this really what they did in Ancient and Medieval times, when the idea of “the grammar stage” was current? I’m not sure whether they ever learned lists of rules or whole paradigms. It’s possible. But this I know: schoolboys in those days memorized living books in Latin and Greek. Books. Syllable by syllable, even if they weren’t yet completely clear on the meaning (let alone the themes and character development). Early Christian monks were troubled that when they tried to pray, their minds would get distracted reciting war scenes from the Iliad or Aeneid that they had learned as children. In the Middle Ages, it was considered standard to know the entire book of Psalms in Latin by heart–that was often a prerequisite for starting dialectic education.3 So all those young children walked in the “fields” of Latin, and absorbed great ideas right along with a feel for what “-ibus” means.

How can we cultivate wonder in our study of Latin grammar today? The first step is to take time with the words, and give our full attention. We need to let ourselves be comfortable with not fully understanding–yet–and enjoy words nonetheless. Enjoy the way they sound and the way they look on a page (or on the wall); help a child to be curious rather than trying to control. The second step is on our Recitations Page. There is no better way to pay attention, to observe closely, to get a real poetic knowledge of something, than to memorize it. Our first Latin memory verse is four words long. Or as a medieval schoolboy would have said, eight syllables. Eight tiny steps out the door and into the fields of wonder.

- James Taylor, Poetic Knowledge (1998)

- Vol. 3, p.162-3

- cf. Mary Carruthers, The Craft of Thought: Meditation, Rhetoric, and the Making of Images, 400-1200 (1998)

- Images are of Priscian’s Latin Grammar in St. Gall, Switzerland: http://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/de/csg/0904/10/0/Sequence-706

Leave a Reply